Consciousness In The Quantum World

It is widely acknowledged that the functioning of the material brain is somehow related to consciousness or, more generally, mental activity. It is reasonable to wonder whether quantum theory can aid in our understanding of consciousness because it is the most fundamental theory of matter that is currently available. We'll review a number of strategies that have been put out in recent decades to answer this issue positively. The three main categories of corresponding approaches are as follows:

(1) Quantum processes in the brain manifest as consciousness

(2) Without referring to brain activity, consciousness can be understood using quantum notions

(3) Matter and consciousness are seen as two sides of the same fundamental reality.

We'll talk about the main modern variations of these quantum-inspired strategies.

They apply quantum theory in various ways and make various epistemological assumptions, it will be noted. Both unfavourable and advantageous aspects of each of the discussed strategies will be emphasised.

The question of the relationship between matter and consciousness has numerous elements, and it can be tackled from a variety of angles. In this regard, philosophy and psychology have historically held the top positions, with behavioural science, cognitive science, and neuroscience later joining them. In addition, the topic has benefited greatly from the fascinating contributions made by quantum physics and the physics of complex systems.

The brain is one of the most complicated systems we are aware of, which is clear when it comes to the complexity issue. Complex systems techniques have greatly helped and will continue to help the research of neural networks, their relationship to the function of single neurons, and other vital problems. Regarding quantum physics, there can be no rational scepticism that quantum events take place and have the same impact on biological systems as they do elsewhere in the material universe.

However, whether these events are effective and pertinent for those components of brain activity that are associated with mental activity is up for debate.

Early 20th-century efforts to link quantum theory to consciousness were primarily driven by philosophical considerations. Given that it is conceivable that conscious free choices, or "free will," are difficult in a world that is entirely predictable, quantum randomness may in fact create new opportunities for free will. (However, randomization poses issues for goal-directed volition!)

In contrast to the deterministic worldview that came before it, quantum theory introduces an element of randomness, and randomness indicates our lack of a more precise description (as in statistical mechanics). In stark contrast to such epistemic randomness, quantum randomness has been thought of as a fundamental aspect of nature, regardless of our ignorance or knowledge, in processes like the spontaneous emission of light, radioactive decay, or other examples. The behaviour of ensembles of these events is statistically determined, whereas this property specifically pertains to individual quantum events. Statistical laws limit the indeterminism of individual quantum events.

The ideas of complementarity and entanglement were additional aspects of quantum theory that attracted discussion of consciousness-related topics. Quantum physics pioneers like Planck, Bohr, Schrodinger, Pauli, and others have highlighted the different ways that quantum theory may play a role in rethinking the long-standing tension between physical determinism and human free will.

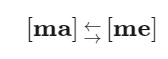

The relationships between mental [me] states of awareness and material [ma] brain states are frequently conceived in a direct manner (A):

This demonstrates a basic paradigm for investigating interactions involving reduction, supervenience, or emergence that can provide both monistic and dualistic images. For instance, the widely accepted position of "strong reduction" holds that all mental states and characteristics can be boiled down to the realm of matter or even to physics (physicalism). According to this perspective, investigating and comprehending the material realm, such as the brain, is both essential and sufficient to comprehend the mental domain, such as awareness. It produces a monistic image in which any need to discuss mental states is immediately erased or at the very least seen as an epiphenomenal phenomenon. From an epiphenomenalist perspective, mind-brain correlations are still valid even though they are causally irrelevant, but eliminative materialism makes even correlations irrelevant.

Qualia arguments, which emphasise the difficulties for physicalist accounts to adequately encompass the quality of the subjective experience of a mental state, or "what it is like to be," are frequently discussed counterarguments against the validity of such strong reductionist methods. As a result, there is an explanatory discrepancy between first- and third-person narratives, which Chalmers refers to as the "hard issue of consciousness." The idea that the physical domain itself is not causally closed is a different, less well-known counterargument. Any method of solving the fundamental equations of motion, including experimental, numerical, and analytical methods, calls for the establishment of boundary conditions and initial circumstances that are not predetermined by the laws of nature. This causal gap holds for both classical and quantum physics, where it is made more difficult by a fundamental indeterminacy brought on by collapse. The challenges of including concepts of the temporal present and nowness in a physical description are the subject of a third category of counterarguments.

However, it is also possible to think about the relationships between mental and physical states in a non-reductive way, such as in terms of emergence relations. If the material brain is not required or not adequate to study and understand mental states and/or qualities, they might be regarded as emergent. By attempting to reduce the mental to the material, one is left with a dualistic vision that is less extreme and more believable than Cartesian dualism. It nearly becomes inescapable to talk about the causal relationship between mental and material states within a dualistic framework of thought. Growing interest has recently been shown in particular in the causative efficacy of mental states upon brain conditions (also known as "downward causation"). In terms of quantum behaviour of the brain, "Quantum Brain" is the most well-known effort along those lines.

Bohr has long held the belief that fundamental aspects of quantum theory, including complementarity, have significant implications for fields outside of physics. Bohr actually learned about complementarity through William James and, more indirectly, psychologist Edgar Rubin, and he quickly saw its potential for quantum physics. Although Bohr was likewise convinced of the additional physical significance of complementarity, he never provided any explicit details on this concept, and no one else did either for a very long time after him. This scenario has altered because several research initiatives now make important quantum theory ideas relevant to fields outside of physics.

Approaches that have been developed to pick up Bohr's idea with regard to psychology and cognitive science are of particular interest for investigations of consciousness. Early in the 1990s, the Aerts group took the initial steps in this area by addressing quantum-like behaviour in non-classical systems using non-distributive propositional lattices. Khrennikov, who focuses on non-classical probabilities, and Atmanspacher, who develops an algebraic framework with non-commuting operations, have proposed alternative strategies. Primas, who addresses complementarity using partial Boolean algebras, and Filk and von Muller, who show connections between fundamental conceptual categories in quantum physics and psychology, are responsible for other lines of reasoning.

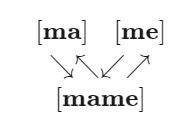

As a substitute for (A), a third category can be used to indirectly conceptualise (B) mind-matter relations:

This third category, here designated [mame], is frequently thought of as being psychophysically neutral with regard to the distinction between [ma] and [me]. Issues of reduction and emergence in scenario (B) relate to the relationship between the distinct elements [ma] and [me] and the undivided "background reality" [mame].

They have a lengthy history dating back to Spinoza and encourage dialogue. Early proponents of psychophysics like Fechner and Wundt supported related ideas. The modern process philosopher Whitehead made reference to the mental and physical poles of "real occasions," which transcend their dual outward manifestations. Many "identity theories" in the Feigl and Smart tradition see mental and material states as essentially the same "core states," though viewed from various angles. Other interpretations of this term have been put forth by Jung and Pauli, who relate to Jung's theory of a psychophysically neutral, archetypal order, or by Bohm and Hiley, who speak of an implicate order that unfolds into the many explicate domains of the mental and the material.

Velmans has created a comparable strategy that is supported by psychological empirical data, while Strawson has offered a "true materialism" that makes use of a roughly equivalent framework. Chalmers, another supporter of dual-aspect thinking, speculates that the fundamental, psychophysically neutral level of description might be best described in terms of information.

It should be highlighted before moving on that many modern techniques prefer to distinguish between first- and third-person views over mental and physical states. This language emphasises the disconnect between immediate conscious sensations (also known as "qualia") and its behavioural, neurological, or biophysical descriptions. Closing the gap between first-person experience and third-person reports of it is referred to as the "hard problem" in consciousness research. In the current contribution, it is implicitly assumed that mental aware states are connected to first-person experience. However, this does not imply that the issue of how to exactly define consciousness is regarded as being solved. In the end, defining a mental state in precise terms will be (at least) as challenging as defining a material state.